What Is Listed Building Consent? A Complete UK Guide

- Harper Latter Architects

- Dec 24, 2025

- 14 min read

If you own, or are thinking about buying, a property that’s officially recognised for its special architectural or historic interest, you’ll soon come across the term Listed Building Consent.

So, what is it? Put simply, it’s a specific type of legal permission you need before making certain changes to a listed property. It's completely separate from standard planning permission and is focused entirely on one thing: protecting the unique character and story of the building.

Understanding What Listed Building Consent Really Means

Owning a piece of the nation’s history is a genuine privilege, but it also comes with a unique set of responsibilities. If your home is listed, you aren't just a homeowner; you're a custodian of a small part of our national heritage.

This is where Listed Building Consent (LBC) comes into play. Think of it less as a bureaucratic hurdle and more as a stewardship agreement. Governed by the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990, LBC is the formal process that protects these treasured properties from alterations that could harm their special character.

Its sole purpose is to manage change in a way that respects and preserves the building's historical and architectural significance for generations to come.

Why Does This Special Consent Exist?

Unlike typical planning permission, which deals with land use and the external appearance of new developments, LBC delves much deeper. It scrutinises any work—both internal and external—that might affect the very fabric and essence of what makes the building special. This could be anything from replacing timber windows to moving an internal wall or even changing a fireplace.

The level of protection is directly linked to the building's listing grade, which tells you just how important it is on a national scale.

To give you a better idea of what these grades mean, here’s a quick breakdown of how buildings are categorised in England.

Listed Building Grades At A Glance

Grade | Percentage of Listings | Description of Significance |

|---|---|---|

Grade I | 2.5% | Buildings of exceptional, outstanding national interest. Think cathedrals and royal palaces. |

Grade II* | 5.5% | Particularly important buildings of more than special interest. |

Grade II | 92% | Buildings of special interest, warranting every effort to preserve them. The most common grade. |

As you can see, the grading system ensures that our most irreplaceable heritage assets are protected with the rigour they deserve. This is why getting the right advice is so important.

A Collaborative Process, Not A Barrier

It’s tempting to see the LBC process as a frustrating barrier, but a better way to view it is as a collaborative dialogue with your local authority’s conservation officer. Their role is to provide expert guidance and help you find ways to make changes that are sensitive and appropriate.

By working with professionals who specialise in conservation and heritage architecture, you can develop proposals that meet your needs while honouring the building’s unique story.

The core principle of Listed Building Consent is to ensure that any change is managed thoughtfully, preserving the historical narrative of the property. It’s about ensuring the building's legacy continues, rather than preventing it from evolving.

Knowing When You Need Listed Building Consent

Understanding the theory behind Listed Building Consent is one thing, but knowing when it actually applies to your project is what really matters. The fundamental rule sounds simple enough: consent is required for any work that could affect a building's special architectural or historic character. This legally covers demolition, alterations, and extensions.

But the phrase ‘affecting character’ is deliberately broad, and it catches a lot of homeowners by surprise. It goes far beyond major structural changes and pulls in many common renovation jobs that might seem minor on the surface.

The key thing to remember is that both the interior and the exterior of the building are protected. Seemingly subtle changes can have a huge impact on the historic fabric that the listing is designed to preserve.

Works That Almost Always Require Consent

While every listed building is unique, some jobs are virtually guaranteed to require LBC. These are the kinds of alterations that directly change or remove the historic fabric of the property, affecting how it looks, feels, and functions.

Here are a few common examples that crop up time and time again:

Replacing Windows and Doors: Swapping original timber sash windows for modern uPVC, or even for a different style of timber window, is a classic example of work needing consent.

Altering Internal Layouts: Taking out or adding internal walls, even non-structural ones, changes the historic plan of the property.

Removing Historic Features: This includes taking out original fireplaces, decorative plasterwork, historic flooring, or built-in joinery like panelling and staircases.

External Surface Treatments: Sandblasting original brickwork, painting previously unpainted stone, or applying modern render can cause irreversible damage and will always need permission.

Extensions and Additions: Any kind of extension, including conservatories, porches, or dormer windows, will require both LBC and, in many cases, separate planning permission.

It's a common misconception that if a feature isn't mentioned in the official listing description, it isn't protected. This is completely wrong. The listing protects the entire building, inside and out, from top to bottom.

The Grey Area: What About Repairs and Redecoration?

This is where things can get a bit murky. As a general principle, genuine like-for-like repairs do not require consent. For example, carefully splicing in a new piece of oak to repair a rotten beam using traditional methods and identical materials would likely be considered a repair.

However, replacing that entire beam with a modern steel equivalent is clearly an alteration, and that would absolutely require consent. Likewise, simple redecoration—like repainting an internal wall with emulsion paint—typically doesn’t need LBC as it’s not harming the historic fabric.

But if that same wall features historic wallpaper or painted murals, covering them over would require consent. The distinction between a ‘repair’ and an ‘alteration’ is a critical one, and getting it wrong can be costly. For a detailed breakdown of this and other nuances, our complete UK listed building planning permission guide offers much deeper insights.

Understanding Curtilage Listing

The protection of a listed building doesn't just stop at its front door. It also extends to the curtilage, which includes other structures and land within the property's boundary that have a historic association with the main building.

This means that outbuildings, garden walls, gates, and even historic garden layouts could be protected under the very same listing, even if they aren't mentioned in the description. The rule of thumb is that this applies to any structure built before 1st July 1948. So, altering or demolishing a protected garden wall requires the same consent as knocking down a wall inside the house itself.

Given these complexities, there’s one piece of advice that overrides all others: always consult your local authority’s conservation officer before you plan any work. An informal chat at an early stage can provide clarity, prevent expensive mistakes, and set your project on the right path from day one.

Navigating The Listed Building Consent Application Process

So, you’ve confirmed that your project needs Listed Building Consent. The next step is the application itself, a formal process that can feel pretty daunting at first glance. It helps to think of it less as a bureaucratic hurdle and more as a structured conversation with your local planning authority. And that conversation should start long before you put pen to paper on any official forms.

The single best thing you can do is seek pre-application advice from the conservation officer at your local council. This early chat is designed to stop you from wasting time, money, and energy on a non-starter. It’s your chance to float your initial ideas, get some expert feedback, and understand any potential red flags before committing to a detailed design. A good pre-application meeting can genuinely set your entire project on a much smoother path.

With that initial guidance in hand, the focus shifts to building a robust and persuasive application. This is more than just filling in a form; it's about making a compelling case that shows you truly understand the building's historic value and how your plans respect it.

Assembling Your Essential Documents

A strong application is built on clear, detailed, and professional documents. Your local planning authority needs to see exactly what you want to do and, crucially, why you want to do it. While the specific list can vary slightly from one council to another, a standard application will always include a few key documents.

Getting these documents right often requires specialist input. To understand the difference an expert can make, take a look at our guide to listed building architects and see how they can manage this process for you.

Your core submission package will almost certainly need to include:

Detailed Architectural Drawings: These aren't just rough sketches. You'll need existing and proposed floor plans, elevations, and sections, all drawn to scale. They must clearly show every single aspect of the proposed change.

Design and Access Statement: This report walks the planners through the thinking behind your design. It covers how the proposal will function, what it will look like, and how it respects the building's character while ensuring it’s accessible to everyone.

Heritage Statement: This is arguably the most critical part of your application. It’s a thorough analysis of the building's historic significance and a detailed assessment of the impact your proposed works will have. It has to justify your approach, proving that any harm is minimal and outweighed by the benefits.

Think of a well-researched Heritage Statement as your opportunity to tell the project's story. It's how you show the conservation officer that you've carefully considered the building's past and are proposing a sensitive and appropriate future for it.

Understanding The Process Logistics

Once your application is ready and submitted via the Planning Portal, a formal consultation period kicks off. One of the few welcome surprises is that, unlike standard planning applications, there is no statutory fee for a standalone Listed Building Consent application. If your project also needs planning permission (for an extension, for instance), a fee will apply to that part of the submission.

The local planning authority has a statutory target of eight weeks to make a decision. During this time, they’ll run a 21-day public consultation. This involves putting up a notice on-site and in a local paper, giving neighbours and any interested parties a chance to comment.

For more significant properties, other organisations will be brought into the conversation. Any work proposed for a Grade I or II listed building must be referred to Historic England, the government's key heritage advisor. Depending on the building's age and style, the relevant National Amenity Societies—like The Georgian Group or The Victorian Society—may also be invited to comment. Their expert opinions carry a lot of weight, making a thoroughly prepared application even more essential.

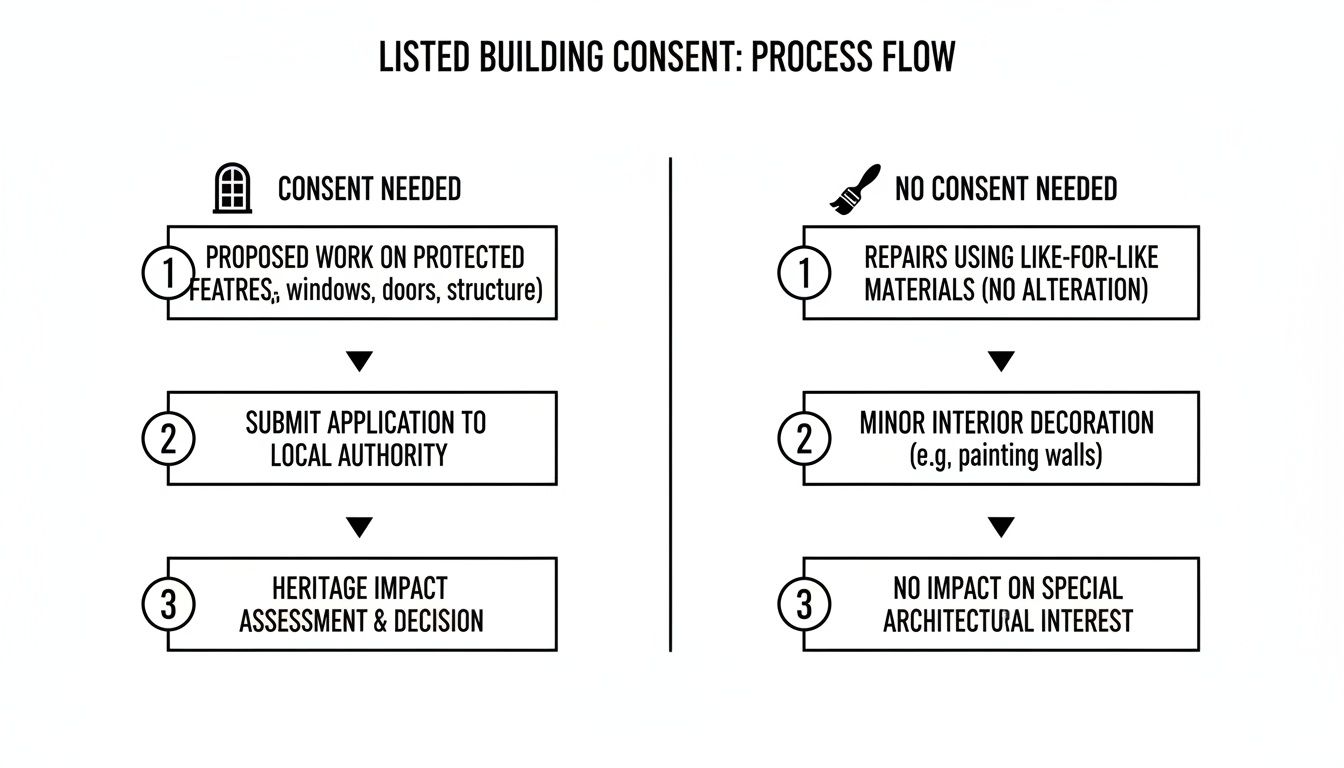

The flowchart below gives a simplified overview of when you’re likely to need consent.

As the visual guide shows, any work that alters a building's historic character requires consent, whereas simple, like-for-like maintenance often flies under the radar.

Managing Timelines, Costs, and Common Pitfalls

Embarking on any project involving a listed building means getting to grips with the time, effort, and money involved. It’s a process with its own unique rhythm and challenges, so setting realistic expectations from day one is the best way to avoid stress and budget blowouts down the line.

The local planning authority has a statutory target of eight weeks to decide on a Listed Building Consent application, but it’s wise to treat this as a best-case scenario. In reality, delays are common. They can crop up for all sorts of reasons, from simple administrative backlogs to more complex back-and-forth negotiations with the conservation officer. An incomplete submission or a request for more detail can easily add weeks, if not months, to the clock.

This is why building a generous buffer into your project schedule isn’t just a good idea—it’s essential. Think of it as a marathon, not a sprint, especially for more significant works.

Understanding the True Costs Involved

While the application for LBC itself is usually free, don't let that fool you. The real investment comes from the professional expertise needed to prepare a convincing application and the specialist craftsmanship required to build it to the right standard.

To get your application over the line, you’ll almost certainly need to budget for professional fees. This could include:

Conservation Architect Fees: To produce the highly detailed drawings, heritage statements, and design documents the council needs to see.

Heritage Consultant Fees: For specialist reports that dig into the building’s history and significance, justifying the impact of your proposed works.

Structural Engineer Fees: A must if your project involves any structural alterations.

Specialist Surveys: Things like bat surveys or timber condition reports are often non-negotiable for historic buildings.

And the costs don't stop once you get approval. Using traditional materials and hiring skilled craftspeople—think stonemasons, lime plasterers, or specialist joiners—often comes at a premium compared to standard construction. Factoring this "heritage premium" into your budget from the start is absolutely vital.

Sidestepping Common Pitfalls

Navigating the LBC process can feel like a minefield, and it’s easy to stumble into a few common traps. Knowing what these are is the first step to avoiding them and making the journey a whole lot smoother.

A 2022 survey by Historic England found that while 81% of listed building owners support the idea of LBC, satisfaction with the actual process has plummeted to just 35%. This points to growing frustration with delays and bureaucracy, which are often linked to simple application mistakes. You can get more insight by reading the full survey from Historic England.

To keep your application on the right track, steer clear of these frequent errors:

Underestimating the Detail Required: One of the main reasons for delay is submitting basic sketches or vague information. Councils need meticulous, scaled drawings and a comprehensive Heritage Statement to make an informed decision. Anything less just won’t cut it.

Proposing Inappropriate Materials: Suggesting modern materials like uPVC windows or cement-based render is a guaranteed way to hit a brick wall. Your plans must champion the use of traditional, breathable, and historically appropriate materials that respect the building's fabric.

Failing to Justify the Changes: A strong application doesn't just show what you want to do; it explains why it's necessary. You need to build a robust, evidence-based case that shows your proposal is well-considered and minimises any harm to the building’s special character.

The most successful applications are those that demonstrate a deep respect for the building's history. They present a clear, well-reasoned argument that balances the owner's needs with the duty to preserve our shared heritage.

Learning from these common mistakes can transform the LBC process from a daunting hurdle into a structured and, ultimately, successful part of your project.

The Real Consequences Of Unauthorised Works

It can be tempting to see the listed building consent process as just another piece of bureaucratic red tape, especially for what feel like minor jobs. But pushing ahead with alterations without the right permissions is a serious misstep, with consequences that go far beyond a typical planning dispute.

Doing any unauthorised work on a listed building isn’t a simple civil matter—it’s a criminal offence under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. That fact alone should tell you how seriously the UK views the protection of its historic architecture.

The penalties are designed to be a real deterrent, not just a slap on the wrist. A conviction can lead to unlimited fines and, in the most severe cases, a prison sentence of up to two years. It's important to know that both the property owner who ordered the work and the builder who carried it out can be prosecuted.

An Enforcement Power Without Time Limits

Here’s one of the most crucial differences between standard planning rules and listed building controls: the enforcement clock never stops ticking. For a normal planning breach, a local authority usually has a four or ten-year window to take action. If they miss it, the work can become lawful.

That safety net does not exist for listed buildings. There is no time limit on enforcement. A council can issue a Listed Building Enforcement Notice five, ten, or even fifty years after the work was done.

This notice will demand that you undo the changes, entirely at your own cost. Imagine the nightmare of having to tear out a modern kitchen to reinstate a period layout, or replacing uPVC windows with historically accurate timber sashes decades after they were fitted. The financial and emotional toll can be immense.

The distinction between these two types of consent is stark, particularly when it comes to enforcement powers. Let's break down the key differences.

Listed Building Consent Vs Standard Planning Permission

Aspect | Listed Building Consent (LBC) | Standard Planning Permission |

|---|---|---|

Enforcement Time Limit | None. Enforcement action can be taken at any point in the future. | Typically 4 years for building works or 10 years for a change of use. |

Type of Offence | Criminal Offence. Can lead to prosecution, fines, and even imprisonment. | Civil Matter. A breach of planning control is not a criminal offence in itself. |

Scope | Covers any alteration, extension, or demolition that affects the building's special character, inside or out. | Governs development, such as new buildings, major alterations, and changes of use. |

Penalties | Unlimited fines and/or up to two years in prison. | An Enforcement Notice requires compliance. Failure to comply is a criminal offence. |

As you can see, the stakes are significantly higher with listed buildings. The perpetual risk of enforcement makes cutting corners a gamble that simply isn't worth taking.

Unlike standard planning permission, which has enforcement time limits of 4-10 years, there is no time limit for enforcement action regarding unauthorised works to a listed building. This perpetual risk means non-compliance can lead to severe penalties, as highlighted in legal cases such as the judicial review concerning the Grade II-listed Christ Church Longcross. Discover more insights on the differences between planning and listed building consent from Burges Salmon.

The Problem Of Passing Liability On

These issues often come to light during the sale of a property. When a buyer's solicitor is doing their due diligence, any unauthorised works will raise a huge red flag, potentially scuppering the whole deal. The problem is that the liability for the work is passed down from owner to owner, meaning whoever buys the house also inherits the risk of future enforcement action.

This creates a chain reaction of problems:

Mortgage Lenders: Most lenders will flat-out refuse to offer a mortgage on a property with a known legal defect like this. Your pool of potential buyers shrinks dramatically.

Devaluation: The property's value will take a significant hit, reflecting the cost of putting things right and the ongoing legal risk.

Insurability: Getting the correct specialist listed building insurance can become much harder, or prohibitively expensive, once unauthorised works are on the record.

Ultimately, any short-term gain from dodging the LBC process is completely overshadowed by the severe and long-lasting risks. The message couldn't be clearer: getting the proper consent isn't just advisable, it's absolutely essential.

Got Questions About Listed Building Consent?

Working with listed buildings often throws up a lot of questions. It's a world filled with specific rules, and it’s easy to feel unsure about what you can and can’t do. To help clear up some of the most common points of confusion, here are the answers to the queries we hear most often.

How Do I Find Out If My Property Is Listed?

Your first port of call should always be the National Heritage List for England (NHLE). This is the official, free-to-use online database managed by Historic England, and it’s the definitive register for every nationally protected historic site.

For absolute certainty, it’s also wise to check with the conservation or planning department at your local council. They hold the official records for every listed property in their patch and can confirm your building's status and grade without any doubt.

Can I Get Retrospective Listed Building Consent?

In a word, no. There's simply no formal process for getting ‘retrospective’ consent. If work has been carried out without permission, you can't just apply for it after the fact. It's treated as a serious criminal offence.

The local planning authority has the power to serve a Listed Building Enforcement Notice, which can force you to reverse all the changes at your own cost. In more serious cases, they can prosecute the person who commissioned the work.

The crucial thing to remember is that not knowing your home was listed is no defence. The responsibility to check and get the right permissions always falls on the property owner before a single tool is lifted.

Do I Need LBC For Energy Efficiency Upgrades?

Yes, it’s almost certain you will. Any alteration that touches the historic fabric or character of a listed building needs consent, and that includes most modern energy efficiency upgrades. Think installing double glazing, adding solar panels, or fitting internal wall insulation – all of these require a formal LBC application.

The good news is that conservation officers are becoming much more open to sensitive, well-designed upgrades. Your proposal will need to clearly show how it will cause minimal harm to the building's historic importance while delivering real benefits.

Who Is Liable For Unauthorised Works: The Owner Or The Builder?

The primary legal responsibility lands squarely on the person who caused the works to be executed. In almost every case, that's the property owner.

While a builder could potentially face prosecution for their part in the work, the owner is the one who is ultimately accountable for making sure all the necessary consents are in place before the project gets underway.

Navigating the complexities of listed building consent requires specialist expertise. Harper Latter Architects offers dedicated conservation and heritage services to guide you through every stage, ensuring your vision respects your property's unique history. To discuss your project, visit https://harperlatterarchitects.co.uk.